II.

FROM THE DOOR OF STONE TO THAT OF IRON.

A whole army driven half wild by its enforced inaction in the presence of danger; four thousand men unable to save three children,—such was the situation.

In point of fact, they had no ladder; the one sent from Javené had not arrived; the flames spread as from a yawning crater; it was simply absurd to attempt to extinguish them with the water from the half-dried brook in the ravine; one might as well empty a glass of water into a volcano.

Cimourdain, Guéchamp, and Radoub had gone down into the ravine. Gauvain had returned to the hall on the second story of the Tourgue, where the turning stone, the secret passage, and the iron door of the library were to be found; it was there that the sulphur match had been lighted by the Imânus, and there the fire had originated.

Gauvain had brought with him twenty sappers. Their last resource was to force open the iron door. Its fastenings were terribly strong.

They went at it with their axes, dealing violent blows. The axes broke. One of the sappers exclaimed,—

"Steel shivers like glass against that iron."

In fact, the door was composed of double sheets of wrought-iron bolted together, each sheet three inches thick.

Then they took iron bars and tried to pry the door open from below. The iron bars broke.

"One would think they were matches," said the sapper.

"Nothing less than a cannon-ball could open that door," muttered Gauvain, gloomily. "We should have to mount a field-piece up here."

"But even then—" replied the sapper.

For a moment they stood in despair, and their arms fell helpless by their sides. With a sense of defeat, these men stood in speechless dismay, gazing upon that door so awful in its immobility. They caught a glimpse of the red reflection from beneath it. Behind them, the fire was spreading.

The frightful body of the Imânus was there, dread victor that he was.

But a few minutes more, and the entire building might fall into ruins.

What could they do? The last ray of hope was gone.

Gauvain, whose eyes were riveted on the revolving stone and the opening through which the escape had been made, cried in the bitterness of his exasperation,—

"And yet the Marquis de Lantenac escaped through that door!"

"And returns," said a voice.

Against the stone setting of the secret passage appeared a white head.

It was the Marquis.

It was many a year since Gauvain had seen him so close at hand. He drew back.

Every man present stood as if petrified.

The Marquis held a large key in his hand; with one haughty glance he compelled the sappers who stood in his path to make way for him, walked at once to the iron door, stooped beneath the arch, and put the key into the lock.

It creaked in the lock, the door opened, they saw the fiery gulf; the Marquis entered it.

With head erect and steady step he strode forward. And those who looked on shuddered as their eyes followed his receding form.

He had barely taken a few steps in the burning hall, before the inlaid floor, undermined by the fire and shaken by his tread, gave way behind him, setting a chasm between him and the door. The Marquis pursued his way, never once turning his head, and vanished in the smoke.

Nothing more was seen.

Had he succeeded in making his way; or had another fiery chasm opened under his feet; or had he but ended his own life? No one could tell. A wall of smoke and flames rose before them. Whether dead or alive, the Marquis was on the other side.

III.

WHERE THE SLEEPING CHILDREN WAKE.

Meanwhile, the little ones had at last opened their eyes.

The fire, although it had not yet reached the library, cast a red reflection on the ceiling. It was not the kind of dawn the children knew. They were gazing at it,—Georgette utterly absorbed.

The conflagration showed forth all its glories; the black hydra and the scarlet dragon appeared amid the smoke-wreaths in all their sombre and vermilion hues. Great sparks shot out into the distance, lighting up the gloom like contending comets pursuing one another. Fire is a prodigal; its furnaces abound in jewels which they scatter to the winds; and it is to some purpose that charcoal is identical with the diamond. From the fissures opened in the wall of the third story, the embers were showering down into the ravine like cascades of jewels; the heaps of straw and oats burning in the granary began to pour in a stream through the windows like avalanches of gold-dust,—the oats changing to amethysts, and the straw to carbuncles.

"Pretty!" cried Georgette.

All three were now sitting up.

"Ah!" cried the mother, "they are awake!"

When René-Jean rose, then Gros-Alain rose also, and Georgette followed.

René-Jean stretched himself, and going towards the window, exclaimed, "I am hot!"

"Me hot!" repeated Georgette.

The mother called them.

"Children! René! Alain! Georgette!"

The children looked round. They were trying to find out what it all meant. Where men feel terrified, children are simply curious; he who is open to surprise is not easily alarmed; ignorance is closely allied to intrepidity. Children have so little claim upon hell, that were they to behold it, it would but excite their admiration.

The mother kept repeating,—

"René! Alain! Georgette!"

René-Jean turned; that voice roused him from his reverie. Children have short memories, but their recollections are swift; the entire past is for them but as yesterday. When René-Jean saw his mother, it seemed to him the most natural thing that could happen, surrounded as he was by strange things; and with a dim consciousness of needing support, he called, "Mamma!"

"Mamma!" said Gros-Alain.

"M'ma!" repeated Georgette.

And she stretched out her little arms.

The mother shrieked, "My children!"

The three children came to the window-ledge; fortunately, the conflagration was not on this side.

"I am too warm," said René-Jean; then added, "it burns"! and he looked for his mother.

"Why don't you come, mamma?" he said.

"Tum, m'ma," repeated Georgette.

The mother, with her hair streaming, torn and bleeding as she was, let herself roll from bush to bush, down into the ravine. There stood Cimourdain and Guéchamp, as powerless in their position as Gauvain was in his. The soldiers, in despair at their helplessness, were swarming around them. The heat would have seemed unbearable, had any one noticed it. They were discussing the escarpment of the bridge, the height of the arches and of the different stories, the inaccessible windows, and the necessity for speedy action. Three stories to climb, with no means of access. Radoub, wounded by a sabre-thrust in the shoulder, his ear lacerated, dripping with sweat and blood, had appeared upon the scene. He saw Michelle Fléchard.

"What have we here,—the woman who was shot come to life again?"

"My children!" cried the mother.

"You are right!" replied Radoub; "this is no time to inquire about ghosts." And he started to scale the bridge,—a useless attempt. He dug his nails into the stone, clung thus for a few seconds, but the smooth layers of stone offered neither cleft nor projection; they were as accurately fitted one upon the other as if the wall had just been built, and Radoub fell back. The fire was still increasing, terrible to behold. They could see the three fair heads framed in the window lighted by the glowing flames. Then Radoub shook his fist towards Heaven as though he beheld some one, and exclaimed,—

"Has Almighty God no mercy?"

The mother, kneeling, clasped her arms around one of the piers of the bridge, crying, "Mercy!"

The hollow sound of crashing timbers mingled with the crackling of the flames. The glass doors of the bookcases in the library cracked and fell with a crash. There could be no doubt that the woodwork was giving way. Human strength was of no avail. One moment, and the entire building would be swallowed up in the abyss. They were only waiting for the final catastrophe. The little voices could be heard repeating, "Mamma, mamma!" They were in paroxysms of terror.

Suddenly against the crimson background of the flames a tall figure came into view standing in the window next to the one where the children stood.

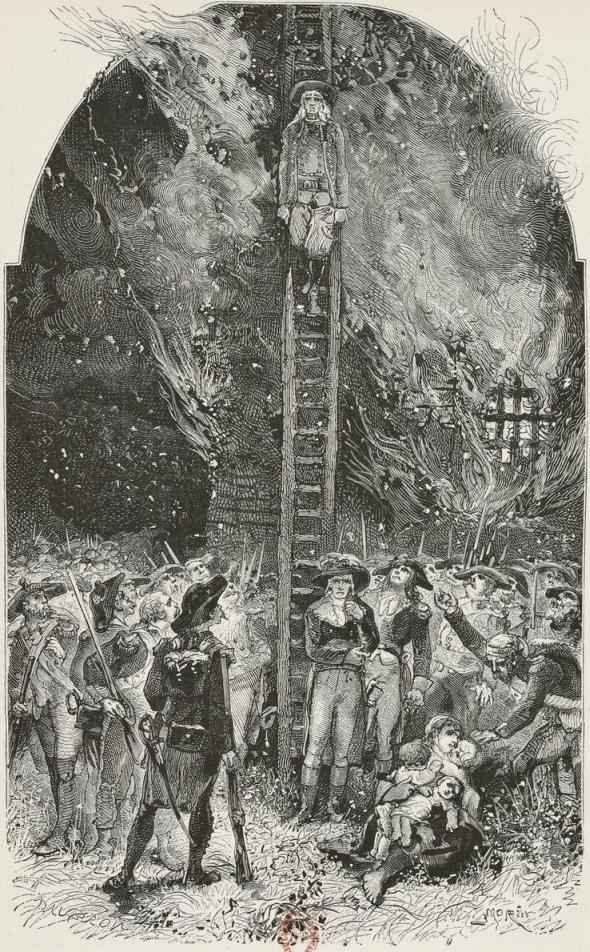

All heads were raised, all eyes were riveted upon the spot. A man up there, in the hall of the library,—a man in that furnace! His face looked black against the flames, but his hair was white. They recognized the Marquis de Lantenac.

He vanished, but only to appear again.

This appalling old man stood in the window, managing an enormous ladder. It was the escape-ladder, which had been lying along the library wall, and which he had dragged to the window. He seized one end of it, and with the masterly agility of an athlete he let it slip out of the window over the outer ledge down into the depths of the ravine. Radoub, standing below, wild with excitement, received the ladder in his outstretched arms, and clasping it to his breast, cried,—

"Long live the Republic!"

"Long live the King!" replied the Marquis.

"You may cry what you please," muttered Radoub, "and talk all the nonsense you like; you are a very angel of mercy."

The ladder was firmly planted, and communication thereby established between the burning hall and the ground. Twenty men, led by Radoub, rushed forward, and in the twinkling of an eye grouped themselves on the ladder from top to bottom, leaning back against the rungs, like masons carrying stones up and down, thus forming a human ladder over the wooden one. Radoub, standing on the uppermost rung, facing towards the fire, was just on a level with the window.

The little army, dispersed across the heath and along the slopes, overcome by contending emotions, hastened towards the plateau down into the ravine and up to the platform of the tower. Again they lost sight of the Marquis, but he reappeared, carrying a child in his arms.

The applause was tremendous.

He had caught up the first child that came within his reach, and it chanced to be Gros-Alain, who cried out,—

"I am frightened!"

The Marquis handed him to Radoub, who passed him on to a soldier standing just behind him, a little farther down, who in his turn delivered him to the next one; and while Gros-Alain, screaming with terror, was thus transferred from hand to hand until he reached the bottom of the ladder, the Marquis, disappearing for a moment, returned to the window with René-Jean, who, struggling and crying, slapped Radoub just as the Marquis handed him to the sergeant.

Again the Marquis went back into the burning room. Georgette was the only one left. She smiled, and this man of granite felt the tears spring to his eyes. "What is your name?" he asked.

"'Orgette," she said.

He took her still smiling in his arms, and as he gave her to Radoub his conscience, austerely pure, albeit darkened, succumbed to the overpowering charm of innocence, and the old man kissed the child.

"It is the little midget!" exclaimed the soldiers; and so Georgette in her turn, amid the cries of admiration, was also passed from hand to hand till she reached the ground. The soldiers clapped their hands and stamped their feet. The old grenadiers sobbed aloud as she smiled upon them.

The mother stood at the foot of the ladder, panting, frantic, intoxicated by this sudden transition from hell to paradise. Excess of joy tears the heart in a fashion of its own. She held out her arms, first receiving Gros-Alain, then René-Jean, then Georgette. She covered them with frenzied kisses; then bursting into a laugh she fell swooning to the ground.

Then rose a loud cry,—

"All are saved!"

And so indeed they were, except the old man.

But no one thought of him, not even he himself perhaps. For several instants he stood dreamily near the window-ledge, as though he would give the fiery abyss time to make up its mind; then deliberately, slowly, and proudly he stepped over the window-sill, and without turning, holding himself upright and perfectly erect, with his back towards the rungs, the conflagration behind and the precipice before and beneath him, with all the majesty of a supernatural being he proceeded to descend the ladder in silence. Those who were on the ladder rushed down; a thrill ran through the witnesses, and they drew back in holy horror before this man who was approaching them like a vision. But stately and grave he continued his descent into the darkness before him, drawing nearer and nearer as they recoiled before his approach. His marble pallor revealed not a wrinkle; his ghost-like eyes, cold as steel, neither glittered nor flashed. As he drew near these men, whose startled eyes were fixed upon him in the darkness, he seemed to grow at every step; the ladder shook and echoed beneath his ominous tread; he might have been compared to the statue of the commander returning to his tomb.

When he reached the bottom and had stepped from the last rung of the ladder to the ground, a hand seized him by the collar. He turned.

"I arrest you," said Cimourdain.

"I approve," replied Lantenac.